Arthroscopic soft tissue findings associated with tibial plateau fractures

Hallazgos artroscópicos en partes blandas asociados a fracturas de la meseta tibial

Resumen:

Antecedentes: cuando se produce una fractura de la meseta tibial (FMT), existe un alto riesgo de lesión de las estructuras de las partes blandas intraarticulares. Estos casos exigen una atención considerable para detectar y diagnosticar estas lesiones. El objetivo de este estudio era realizar una revisión epidemiológica y evaluar la frecuencia de las lesiones de partes blandas asociadas a las fracturas de la meseta tibial (Schatzker I, II y III) identificadas mediante artroscopia. El objetivo secundario consistía en analizar la relación existente entre la frecuencia de las lesiones de las partes blandas y el patrón de la fractura.

Pacientes y métodos: desde junio de 2008 hasta octubre de 2018, se revisó retrospectivamente a 40 pacientes con FMT cerrada Schatzker I, II o III tratados mediante reducción y fijación interna asistidas por artroscopia para evaluar la frecuencia de las lesiones asociadas de partes blandas.

Resultados: la muestra incluyó a 33 hombres y 7 mujeres, con una media de edad de 43,2 años. Se trataba de 9 de tipo I (separación), 28 de tipo II (separación y hundimiento) y 3 de tipo III (hundimiento) según la clasificación de Schatzker. De los 40 pacientes incluidos, 31 tenían una lesión de partes blandas asociada que se detectó mediante artroscopia (77,5%). Se observaron desgarros meniscales en 26 de los 40 pacientes (15 lesiones del menisco lateral y 11 del menisco medial). La tasa más elevada de desgarros meniscales se observó en la FMT de tipo II (tipo I: 15,3%; tipo II: 80,7%; tipo III: 4%). Se observaron 5 roturas del ligamento cruzado anterior (LCA) en las fracturas de tipo II. Los desgarros meniscales fueron la lesión de partes blandas más frecuente.

Conclusión: la FMT se asocia con bastante frecuencia a lesiones de partes blandas en más de la mitad de los casos (77,5%). Las lesiones meniscales constituyen la lesión simultánea más prevalente. La fractura de meseta tibial más común fue la de tipo Schatzker II, que fue la fractura que presentaba un mayor índice de lesiones de partes blandas asociadas.

Nivel de evidencia: IV, estudio observacional retrospectivo de serie de casos.

Relevancia clínica: destacar la relevancia de la asistencia artroscópica en las fracturas de meseta tibial con el objetivo de diagnosticar lesiones de partes blandas que podrían pasar desapercibidas.

Abstract:

Background: when a tibial plateau fracture (TPF) takes place, there is a high risk of injury to intra-articular soft tissue structures. Considerable attentiveness is called for in these cases to identify and diagnose these injuries. The aim of this study was to perform an epidemiological review and assess the frequency of soft tissue injuries associated with tibial plateau fractures (Schatzker I, II and III) identified through arthroscopy. The secondary purpose was to analyze the relationship between frequency of soft tissue injury and the fracture pattern.

Patients and methods: from June 2008 to October 2018, 40 patients with a closed TPF Schatzker I, II or III treated with arthroscopically assisted reduction and internal fixation were retrospectively reviewed to assess the frequency of the associated soft tissue injuries

Results: the sample included 33 men and 7 women, with an average age of 43.2 years. They included 9 of type I (split), 28 of type II (split and depression) and 3 type III (depression) in the Schatzker classification. Of the 40 patients included, 31 had an associated soft tissue lesion detected through arthroscopy (77.5%). Meniscal tears were noted in 26 of the 40 patients (15 lateral and 11 medial meniscus injuries). The highest meniscal tear rate was seen in the type II TPF (type I: 15.3%; type II: 80.7%; type III: 4%). Five ACL ruptures were seen in the type II fractures. Meniscal tears were the most frequent soft tissue lesion.

Conclusion: the TPF is quite frequently associated with soft tissue injuries in more than half of the cases (77.5%). Meniscal injuries constitute the most prevalent concurrent lesion. The most common tibial plateau fracture was Schatzker type II, which was the fracture with the highest associated soft tissue injury rate.

Level of evidence: IV, retrospective observational case series study.

Clinical relevance: highlight the relevance of arthroscopic assistance in tibial plateau fractures with the aim of diagnosing soft tissue injuries that might be overlooked.

Introduction

Proximal tibial fractures represent one of the most studied entities in orthopedic surgery regardless of its relative low incidence (1.6% of all adult fractures in China)(1).

When a tibial plateau fracture (TPF) takes place, there is a high risk of intra-articular soft tissue structure injury(2). Therefore, the decision to perform surgery should not be made by only considering the displacement of the articular surface, but also the involvement of the soft tissue.

The magnitude of the trauma, the position of the of the leg at the time of injury(3), and the bone quality(4,5) determine the fracture type and extent of soft tissue damage. Numerous structures surrounding the knee can be at risk. They include the menisci, collateral and cruciate ligaments and the neurovascular bundle. Considerable attentiveness is called for in these cases to identify and diagnose these injuries since they may be masked by the main lesion, which is the fracture. Accordingly, they are sometimes diagnosed later on in the rehabilitation period when the patient complains about additional symptoms that were not reported prior to the surgery.

Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been reported to have a high sensitivity in detecting associated injuries, the initial pre-operative evaluation may not reveal of soft tissue lesions due to the interference of fracture hematoma and the loss of the normal anatomical structure. Therefore, a concurrent arthroscopic procedure with direct visualization of the joint can help to fully reveal all the structures that were compromised.

The aim of this study was to perform an epidemiological review and assess the frequency of the soft tissue injuries associated with a TPF (Schatzker I, II and III) identified through arthroscopy. The secondary purpose was to analyze the relationship between frequency of soft tissue injury and the fracture pattern. Our hypothesis was that arthroscopically assisted evaluation in TPF would reveal a high frequency of concomitant soft tissue injuries that may go unnoticed in preoperative planning in each Schatzker classification assessed.

Methods

The retrospective review included a total of 40 consecutive patients with lateral closed TPF treated with arthroscopically assisted reduction and internal fixation. It was carried out in 2 different centers between June 2008 and October 2018. Schatzker's classification(6) was used for the categorization of the fractures. For this study, the inclusion criteria were: a) closed TPF Schatzker I, II or III (split, split-depression and depression) because they share similar biomechanical characteristics; b) patients aged over 18 years of age; c) closed reduction and internal fixation combined with arthroscopic examination; and d) fractures confirmed by computed tomography (CT) scans. The exclusion criteria were: a) other types of tibial plateau fractures; b) non-operative cases (usually reserved for non-displaced fractures); c) previous surgery on the ipsilateral knee; d) open fractures; and e) skeletally immature patients.

Indications and timing of surgery

The operative indications included a depression of > 3 mm and/or > 3 mm of displacement and/or a difference of 5° in the anatomic femoral/tibial axis between the injured and uninjured sides(7).

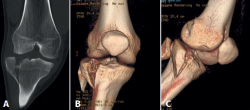

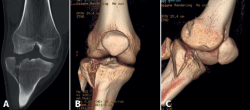

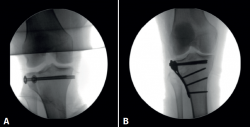

Injured knees always undergo anteroposterior and lateral plain radiographs. A CT scan is also essential for diagnosis, fracture pattern characterization (Figure 1), and surgery planning.

When it is possible, tibial plateau fractures are addressed with immediacy, generally within less than 3 weeks of occurrence. However, intervention is delayed in some cases where the knee developes significant swelling along with notable loss of range-of-motion (less than 90° of flexion to extension) or there is considerable soft tissue damage. Once the swelling improves, arthroscopically assisted reconstruction and minimally invasive internal fixation is performed.

Surgical technique

In cases of TPF with associated intra-articular soft tissue injury, arthroscopy helps to determine the optimal treatment option. Those injuries are repaired before or after fracture fixation, depending on the type of lesion.

The patient is placed supine on the operating table and general anesthesia is administered. A bilateral knee examination is performed while under anesthesia. A well-padded high-thigh tourniquet is placed on the operative leg and a bump is placed under the knee so that it rests at approximately 30° of flexion. The contralateral leg is secured to the table in full extension with a leg holder and a pneumatic compression device is placed around the lower leg to prevent clot formation.

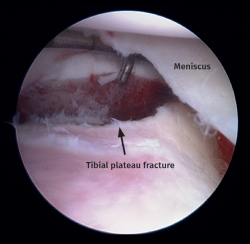

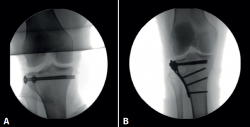

Standard anterolateral and anteromedial portals are created adjacent to the patellar tendon and the joint is visualized with a 30° arthroscope while the knee is insufflated with normal saline. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed to confirm the TPF, the step-off and the presence of associated lesions (Figure 2). An arthroscopic shaver is inserted into the knee to clear the debris and improve visualization. Next, a small longitudinal anterolateral skin approach is performed, and the fractures are fixed with cancellous screws and/or a buttress plate applied on the external side (minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis), according to the type of fracture diagnosed (Figure 3). Arthroscopy is used to assist reduction and, when needed, to treat soft tissue injuries. The senior authors prefer to perform meniscal repair or partial meniscectomy before bone fixation due to the better visualization of the meniscus. Conversely, ligamentous reconstructions are performed after arthroscopically assisted fixation to ensure bony stability.

After TPF osteosynthesis, a varus/valgus stress test and Lachman's test are performed on the injured extremity. Surgical repair is planned in cases of lateral collateral ligament (LCL) and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury. No additional surgery is considered in cases of suspected medial collateral ligament (MCL) lesion, except in patients with avulsion tears.

The cases of soft tissue injuries were documented and their association with each Schatzker classification was then analyzed.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS software package (version 24.0, IBM Corp., USA) was used for the statistical analysis. An analysis of variance, a Chi-Square test, and Fisher’s exact test were used for the statistical analysis. For all the tests, P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

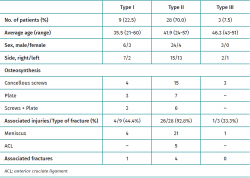

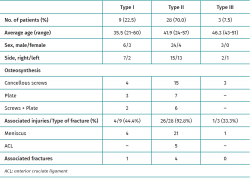

The sample included 33 men and 7 women, with an average age of 43.2 years (range, 21 to 60 years). Twenty-four fractures were on the right, and 16 were on the left. All 40 fractures were in 40 different patients. The injury causing mechanisms were as follows: 21 motor vehicle accidents, 11 falls, and 8 sports related activities. Table 1 lists the patient demographics.

Fracture characteristics

In accordance with the Schatzker classification, 9 type I (split), 28 type II (split and depression) and 3 type III (depression) TPF were identified (Table 1) . No statistical relationship was observed between fracture type and patient age, sex and the injured side.

In the present series, 31 of 40 patients with a Schatzker I, II and III TPF showed associated soft tissue damage detected through arthroscopy (77.5%) (Table 1). All the soft tissue injuries were in different patients. The most common fracture pattern (type II) was seen to have a significantly higher soft tissue injury frequency (92.8%) compared to the other types included in this study (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Associate findings

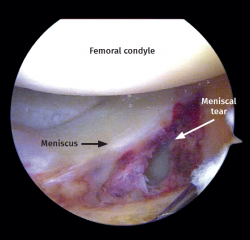

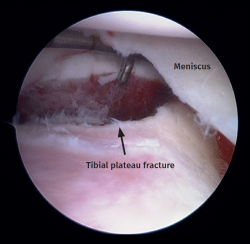

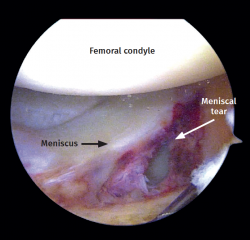

Meniscal tears were the most frequent soft tissue lesion (Figure 4), noted in 26 of the 40 patients evaluated (65.0%). The highest meniscal tear rate was seen in type II tibial plateau fractures (type I: 15.3%; type II: 80.7%; type III: 4%). Table 1 shows the number of meniscal injuries for each fracture type.

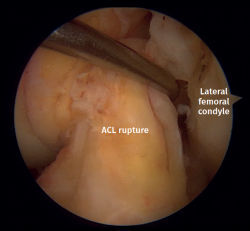

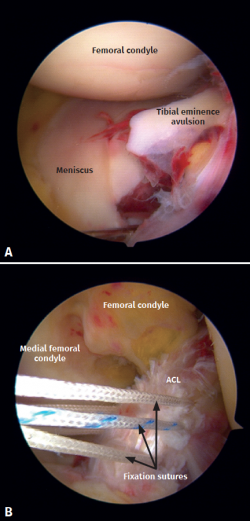

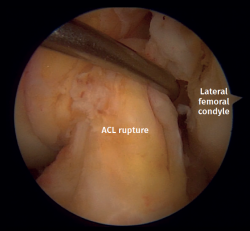

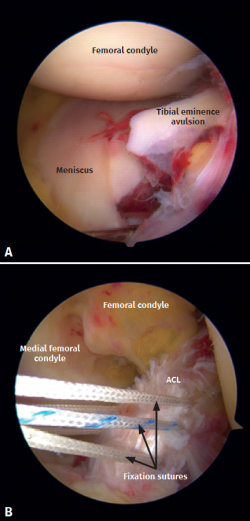

Five ACL ruptures were diagnosed in type II fractures, with 4 complete ligamentous tears (total disruption of fibers) found during arthroscopy (Figure 5). In addition, there was 1 displaced tibial eminence avulsion fracture (McKeever II)(8) (Figure 6A). PCL, LCL and MCL injuries were not found in this cohort. Likewise, neurovascular structures remained intact in all the cases studied.

In addition to those found in the knee (12.5%), 5 of the 40 patients with TPF had experienced some other associated fracture and/or some soft tissue damage. All associated injuries corresponded to the type II Schatzker classification (1 femur + wrist fractures, 1 wrist fracture, 1 hand fracture, 1 humerus fracture, 1 forearm fracture, and 1 patient suffered deep facial tissue abrasion).

Treatment

Treatment was performed depending on the type of lesion.

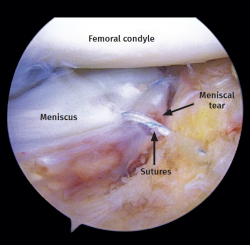

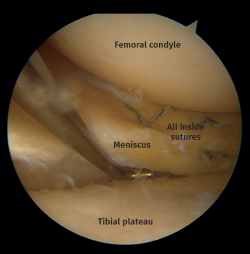

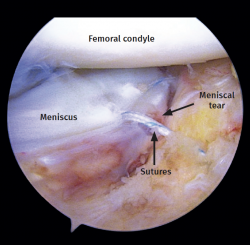

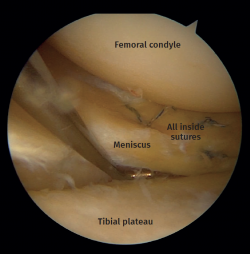

Of the 15 lateral meniscus injuries, there were 9 radial tears treated with partial meniscectomy and 6 peripheral tears that were sutured with a combination of an outside-in and an all-inside technique (Figures 7 and 8).

The remaining 11 lesions involve the medial meniscus (8 radial and 3 flap tears). In all cases, a partial meniscectomy was performed.

All ligamentous disruptions required arthroscopically assisted reduction and minimally invasive fixation of the fracture followed by ACL reconstruction with a hamstring autograft. The displaced tibial eminence avulsion received arthroscopic treatment with a suture fixation technique (Figure 6B).

Discussion

Intra-articular proximal tibial fractures are complex injuries associated with a variety of patterns and a wide range of soft tissue damage. The main finding of this study was that TPF is quite frequently associated with soft tissue injuries (77.5%). Meniscal tears were the most commonly associated soft tissue lesion, with a frequency of 65.0%, being more predominant Schatzker type II (80.7%). Furthermore, the most common TPF identified in this series was Schatzker type II (70.0%), and this pattern had the highest soft tissue damage rate (92.8%).

Soft tissue involvement in the setting of TPF is commonly due to the limited coverage of the knee joint. In this regard, joint blisters, open wounds, and compartment syndrome can dramatically change the timing of surgery, the treatment indication and the overall prognosis of the patient.

Classically, the incidence of associated soft tissue injury in TPF diagnosed by means of physical examination or an intraoperative finding during fixation that has been reported in the literature was 7 to 50%(9,10,11,12,13) In 1977, Schatzker et al.(6) reported an incidence of 8.5% for ligamentous injuries in TPF diagnosed through physical examination and/or an operative finding during surgery. Similarly, Honkonen(11) published an 8% rate of concurrent ligamentous lesions and a 50% rate of meniscal tears in 76 patients with TPF.

MRI has been widely described as the most useful diagnostic imaging method for soft tissue damage in the knee. The incidence of soft tissue injury in TPF diagnosed with MRI reported in the literature is 48 to 99%(14,15,16,17). Colletti et al.(14) published a 45% rate of lateral meniscal damage, 21% with medial meniscal tear, 55% for MCL lesion, 34% for LCL injury, 41% of ACL damage, and 28% for PCL tears after an evaluation of 29 TPF by means of MRI. In a more recent study, Gardner et al.(15) reported a 99% incidence of associated soft tissue injury in 103 TPF diagnosed with MRI. However, this imaging method can overestimate the presence of concomitant lesions in the acute setting.

In various arthroscopic series, the incidence of associated soft tissue damage diagnosed by means of arthroscopy rises from 50 to 57%(18,19,20,21). Hung et al. published a 38% rate of ACL injury, 19% of collateral ligament damage, and a 31% incidence of lateral meniscus injury in an arthroscopic evaluation of 31 TPF(18). Chang et al. published a 52.9% rate of meniscus lesion and a 22.5% cruciate ligament injury rate in an arthroscopic evaluation of 102 TPF(19). In an investigation of arthroscopically assisted reduction and internal fixation of 20 cases with proximal tibial fractures, Glabbeek et al.(20) revealed that 50% of the patients developed a soft tissue injury, with meniscal tears at 35% of and ACL damage at 15%. Additionally, Wang et al.(21) reported that the overall incidence of ACL and PCL tears was 80 and 36%, respectively. Nine (36%) patients sustained ACL footprint avulsions and 3 (12%) had complete ACL tears. A total of 19 (76%) patients had LCL injuries, and 15 (64%) had MCL injuries. The incidence of lateral meniscus tears was 48%, while that of medial meniscus tears was 4%(22). Although the incidence of ACL tears concurrent with a TPF in our series was lower (13.6%), the incidence of meniscal pathology was comparable.

It is well established that TPF and associated soft tissue damage are diagnosed with a comprehensive combination of clinical examination, radiography, CT scans and MRI. Then, arthroscopy confirms the previous findings. Therefore, arthroscopy provides a safe, accurate and quick method of treatment even though it is not necessary to reach this diagnosis.

Arthroscopically assisted fracture management has been advocated as a possible adjunct to the operative treatment of TPF since it may result in enhanced visualization and therefore more accurate reduction(23). A recent study compared arthroscopic assisted reduction and internal fixation (ARIF) with open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) treatment. In their series of 100 consecutive patients, an intra-articular injury incidence of 69% was found(24). Of note, the authors concluded that no differences were encountered between ARIF and ORIF treatment in Schatzker type I fractures. They found ARIF treatment preferable when meniscal tears were present as it presented the opportunity for simultaneous treatment. In cases of Schatzker II, III and IV fractures, there was a small difference in clinical outcomes in favour of ARIF but it was not statistically significant(24).

Similarly, in a comparative retrospective study of 40 patients, Verona et al. reported that both ARIF and ORIF provided a satisfactory outcome for the treatment of Schatzker I-III TPF. However, ARIF led to better clinical results than ORIF(25).

A study performed by Kampa et al. on 25 patients with arthroscopic-assisted fixation of TPF (average follow up of 2.5 years) demonstrated good to excellent outcomes at final follow-up(26). Only an 18% complication rate was found (50% hardware removal and 50% deep venous thrombosis)(26). Chan et al. reported good to excellent clinical and radiologic outcomes in 96% of patients at a mean 87 months. Schatzker fracture types did not differ with regard to the Rasmussen score system or satisfaction outcomes. Secondary degenerative changes were found in 19% of the patients(27). Similarly, Rossi et al. reported that the Rasmussen radiologic assessment score was excellent in 11%, good in 85% and fair in 4% of 46 patients at the 5-year follow-up.

We acknowledge some limitations to this study. First, there are the restraints associated with the retrospective nature of the study design and its multicentric character. Moreover, the relatively small sample and the heterogeneity derived from different surgical teams might have played a role in the final diagnosis assessment.

Conclusion

In the evaluated sample, TPF are highly associated with soft tissue injuries in more than half of the cases (77.5%), of which meniscal injuries constitute the most prevalent concurrent lesion. Importantly, the most common TPF was Schatzker type II (70.0%), which was the fracture with the highest associated soft tissue damage rate (92.8%). A thorough evaluation of the patients with a combination of imaging techniques, diagnosis by means of arthroscopy and therapeutic arthroscopy is called for to address the pathology in a timely manner.

Figuras

Figure 1. Right knee. Schatzker II close tibial plateau fracture. A: coronal computed tomography (CT) scan; B and C: 3-D tibial plateau fracture reconstruction.

Figure 2. Right knee, Schatzker II tibial plateau fracture. Step-off arthroscopic view from the anteromedial portal. Probe placed in the anterolateral portal.

Figure 3. Schatzker I tibial plateau fracture fixed with cancellous screws (A) and Schatzker II tibial plateau fracture treated with a buttress plate (B) applied to the external side.

Figure 4. Left knee. View from the anterolateral portal. Peripheral longitudinal tear involving the lateral meniscus body.

Figure 5. Left knee anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture. View from the anterolateral portal. Probe placed in the anteromedial portal.

Figure 6. A: tibial eminence avulsion fracture McKeever II; B: arthroscopic treatment with a suture fixation technique of the tibial eminence avulsion fracture. ACL: anterior cruciate ligament.

Figure 7. Left knee. View from the anterolateral portal. Peripheral longitudinal meniscus tear suture.

Figure 8. Right knee. View from the anteromedial portal. Probe placed in the anterolateral portal. Peripheral longitudinal meniscus tear sutured with an all-inside technique.

Tablas

Información del artículo

Cita bibliográfica

Autores

Maximiliano Ibañez Malvestiti

Institut Català de Traumatologia i Medicina de l'Esport (ICATME). Hospital Universitari Dexeus. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB)

Jorge Chahla

Rush University Medical Center. Chicago, United States

Juan Erquicia

Departamento de Cirugía Ortopédica. Consorci Sanitari de l’Anoia. Igualada, España

ICATME. Hospital Universitari Quirón-Dexeus. Barcelona, España

Hospital Universitario Dexeus. Grupo Quirónsalud. Barcelona

Harold Simesen de Bielke

Sanatorio Modelo de Tucumán. Argentina

Sebastian Sasaki

Sanatorio Fitz Roy. Buenos Aires, Argentina

Santiago Svarzchtein

Sanatorio Fitz Roy. Buenos Aires, Argentina

Joan Carles Monllau

ICATME. Hospital Universitari Quirón-Dexeus. Barcelona, España

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Barcelona, España

Cirurgía Ortopédica y Traumatología, Hospital del Mar-Parc de Salut Mar, Barcelona, España

IMIM. Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute. Barcelona

Alberto Cid Casteulani

Sanatorio Fitz Roy. Buenos Aires, Argentina

Ethical responsibilities

Conflicts of interest. The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Financial support. This study has received no financial support.

Protection of people and animals. The authors declare that this research has not involved studies in humans or in animals.

Data confidentiality. The authors declare that the protocols of their centre referred to the publication of patient information have been followed.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Referencias bibliográficas

-

1Chen W, Lv H, Liu S, et al. National incidence of traumatic fractures in China: a retrospective survey of 512 187 individuals. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(8):e807-17.

-

2Deng X, Hu H, Wang Y, Shao D, Zhang Y. Arthroscopically assisted evaluation of frequency and patterns of meniscal tears in operative tibial plateau fractures: a retrospective study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021 Feb 6;16(1):117.

-

3Kennedy JC, Bailey WH. Experimental tibial-plateau fractures. Studies of the mechanism and a classification. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1968;50(8):1522-34.

-

4Foltin E. Bone loss and forms of tibial condylar fracture. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1987;106(6):341-8.

-

5Foltin E. Osteoporosis and fracture patterns. A study of split-compression fractures of the lateral tibial condyle. Int Orthop. 1988;12(4):299-303.

-

6Schatzker J, McBroom R, Bruce D. The tibial plateau fracture. The Toronto experience 1968-1975. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979(138):94-104.

-

7Bennett WF, Browner B. Tibial plateau fractures: a study of associated soft tissue injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 1994;8(3):183-8.

-

8Meyers MH, McKeever FM. Fracture of the intercondylar eminence of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52(8):1677-84.

-

9Blokker CP, Rorabeck CH, Bourne RB. Tibial plateau fractures. An analysis of the results of treatment in 60 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984(182):193-9.

-

10Honkonen SE. Indications for surgical treatment of tibial condyle fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(302):199-205.

-

11Honkonen SE. Degenerative arthritis after tibial plateau fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(4):273-7.

-

12Moore TM, Patzakis MJ, Harvey JP. Tibial plateau fractures: definition, demographics, treatment rationale, and long-term results of closed traction management or operative reduction. J Orthop Trauma. 1987;1(2):97-119.

-

13Tscherne H, Lobenhoffer P. Tibial plateau fractures. Management and expected results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993(292):87-100.

-

14Colletti P, Greenberg H, Terk MR. MR findings in patients with acute tibial plateau fractures. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 1996;20(5):389-94.

-

15Gardner MJ, Yacoubian S, Geller D, et al. The incidence of soft tissue injury in operative tibial plateau fractures: a magnetic resonance imaging analysis of 103 patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(2):79-84.

-

16Holt MD, Williams LA, Dent CM. MRI in the management of tibial plateau fractures. Injury. 1995;26(9):595-9.

-

17Kode L, Lieberman JM, Motta AO, Wilber JH, Vasen A, Yagan R. Evaluation of tibial plateau fractures: efficacy of MR imaging compared with CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163(1):141-7.

-

18Hung SS, Chao EK, Chan YS, et al. Arthroscopically assisted osteosynthesis for tibial plateau fractures. J Trauma. 2003;54(2):356-63.

-

19Chang H, Zheng Z, Shao D, Yu Y, Hou Z, Zhang Y. Incidence and radiological predictors of concomitant meniscal and cruciate ligament injuries in operative tibial plateau fractures: a prospective diagnostic study. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):13317.

-

20Van Glabbeek F, van Riet R, Jansen N, D'Anvers J, Nuyts R. Arthroscopically assisted reduction and internal fixation of tibial plateau fractures: report of twenty cases. Acta Orthop Belg. 2002;68(3):258-64.

-

21Wang Y, Cao F, Liu M, Wang J, Jia S. Incidence of Soft-Tissue Injuries in Patients with Posterolateral Tibial Plateau Fractures: A Retrospective Review from 2009 to 2014. J Knee Surg. 2016;29(6):451-7.

-

22Wang CJ, Weng LH, Hsu CC, Chan YS. Arthroscopic single- versus double-bundle posterior cruciate ligament reconstructions using hamstring autograft. Injury. 2004;35(12):1293-9.

-

23Gross SC, Tejwani NC. The Role of Arthroscopy in the Management of Tibial Plateau Fractures. Bull Hosp Jt Dis (2013). 2015;73(2):128-33.

-

24Dall'oca C, Maluta T, Lavini F, Bondi M, Micheloni GM, Bartolozzi P. Tibial plateau fractures: compared outcomes between ARIF and ORIF. Strategies Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2012;7(3):163-75.

-

25Verona M, Marongiu G, Cardoni G, Piras N, Frigau L, Capone A. Arthroscopically assisted reduction and internal fixation (ARIF) versus open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) for lateral tibial plateau fractures: a comparative retrospective study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019 May 24;14(1):155.

-

26Kampa J, Dunlay R, Sikka R, Swiontkowski M. Arthroscopic-Assisted Fixation of Tibial Plateau Fractures: Patient-Reported Postoperative Activity Levels. Orthopedics. 2016;39(3):e486-491.

-

27Chan YS, Chiu CH, Lo YP, et al. Arthroscopy-assisted surgery for tibial plateau fractures: 2- to 10-year follow-up results. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(7):760-8.

Descargar artículo:

Licencia:

Este contenido es de acceso abierto (Open-Access) y se ha distribuido bajo los términos de la licencia Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND (Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional) que permite usar, distribuir y reproducir en cualquier medio siempre que se citen a los autores y no se utilice para fines comerciales ni para hacer obras derivadas.

Comparte este contenido

En esta edición

- Why the AEA endorses the REACA

- The cortical double button fixation system with posterior guide for anterior arthroscopic bone block allows precise graft positioning

- Injuries of the subscapularis: prevalence of partial lesions and their diagnostic difficulty

- Arthroscopic soft tissue findings associated with tibial plateau fractures

- Radiological classifications and assessment scales for Achilles tendinopathy

- Recurrent anteroinferior dislocation of the shoulder. Essential articles

- Stabilization of <em>os acromiale</em> with cannulated screws and high-resistance sutures

- Anterior arthroscopic bone block with double cortical button fixation system and posterior guide for anterior shoulder instability with glenoid defect. Surgical technique

- Proximal avulsion of the extrinsic volar radiocarpal ligaments following radiocarpal dislocation

Más en PUBMED

Más en Google Scholar

Revista Española de Artroscopia y Cirugía Articular está distribuida bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional.