Introduction

Rotator cuff ruptures can present in different degrees, and it is up to each individual surgeon to choose the most adequate treatment. In the case of irreparable ruptures, the options range from the most simple techniques (which will be dealt with in this chapter) such as debridement, tenotomy of the long portion of the biceps (LPB) and partial repair, to interpositioning techniques and tendon transfers or reverse shoulder prostheses (which will be addressed in the following chapters).

Usually, when choosing a treatment, the most extreme decisions are the easiest to make; it is normally not doubted that a young patient with irreparable rupture will need some type of surgery, while in elderly individuals (over age 75) a more conservative approach would seem logical. However, the problem lies with those active patients in the grey zone between 50-70 years of age, with irreparable rupture. In these cases we must decide what, how and why to prescribe a given type of operation, and this requires broad knowledge of the different techniques and treatment options, since there is no preferred technique for this disease condition. This context represents the main focus of the present monographic number of the journal.

The concept "irreparable rupture" must be correctly used, since it is often mixed with the term "massive rupture"; this can lead to error, since not all massive ruptures are irreparable. In effect, irreparable rupture is defined as a lesion in which the tendon cannot be repaired and taken to its insertion footprint in a primary manner based on the usual repair techniques, in view of its size, retraction or muscle condition due to atrophy or adipose infiltration(1).

Clinically, patients with irreparable ruptures may be asymptomatic, and when symptoms do appear they usually consist of pain that increases at night and with movements above head level - though pain has not been shown to be correlated to severity of the condition. Other symptoms include weakness and reduced active range of motion(2).

There are no high levels of evidence regarding the available techniques, and the recommendations are based on retrospective case series, surgeon experience and expert opinions(3).

When dealing with injuries of this kind, the surgeon must seek to restore the patient to his or her condition before the loss of function.

Arthroscopic debridement

Arthroscopic debridement, along with subacromial decompression, would be indicated in patients with a painful active range of motion after conservative management. It also would be indicated in elderly individuals, patients with systemic diseases, or subjects that are improving in the context of a rehabilitation program, due to the synergic effects obtained after arthroscopy(4).

Debridement and subacromial decompression was first introduced by Rockwood(5) in 1988, who described it in the context of open surgery. In his series of 93 patients, no functional deterioration or degenerative changes were recorded after 8 years of follow-up. The same author subsequently(6) published a study in which the technique was performed via arthroscopy in 50 patients, with good outcomes in 83% of the cases after 6.5 years of follow-up. Gartsman(7), in a similar sample, found that 78% of the patients reported improvement after surgery, with a decrease in pain, and improved range of motion and activities of daily living.

In a recent systematic review(8), the main benefit afforded by arthroscopic debridement was seen to be improved range of motion (abduction and flexion) and lessened pain compared with other treatments, though with an arthroplasty conversion rate of 15.4%, which was greater than with other alternatives.

The American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) society(9) concluded that arthroscopic debridement and/or partial repair may be an acceptable management option in patients with irreparable rupture of the rotator cuff, regardless of age, with an intact or repairable subscapularis, no dynamic instability, a low functional demand and no pseudo-paralysis.

One of the most important points when proposing this treatment to patients is to ensure that they understand that the aim of the technique is above all to secure pain relief, but that they should not expect an increase in strength after the operation(10). Some authors(11) have related the degree of previous flexion to the outcomes. The lesser the previous degree of flexion, the poorer the outcomes after debridement. They also used it as a predictor of conversion to arthroplasty in patients with less than 90º of previous flexion, with a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 71%.

As in any procedure, adequate management of the patient expectations is crucial for the success of any kind of surgery.

Tenotomy of the long portion of the biceps

Tenotomy of the LPB associated to arthroscopic debridement remains a controversial decision(12), even in patients with irreparable rupture of the rotator cuff.

Tenotomy or tenodesis of the LPB has been found to be an effective alternative for improving pain in both cuff repair and in certain irreparable ruptures(13).

Prospective studies have shown tenotomy of the LPB to be associated with a greater percentage of Popeye deformity and cramps than tenodesis(14), though no studies have evidenced differences in terms of the functional outcomes(15).

In a comparative study of tenotomy versus only debridement, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups over a mean follow-up of 31 months, in terms of degenerative changes or ascent of the head(16). More recently, Pander et al.(17) recorded similar results in relation to tenotomy of the LPB versus no tenotomy.

Boileau(18) obtained good results with tenotomy or tenodesis of the LPB in the management of pain and dysfunction produced by irreparable rupture of the cuff associated to biceps injury. This author highlighted pseudo-paralysis and severe arthropathy as contraindications to this procedure.

Partial repair of the rotator cuff

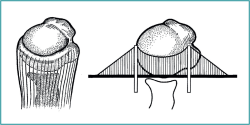

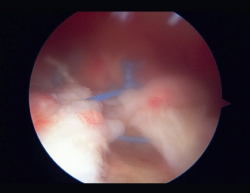

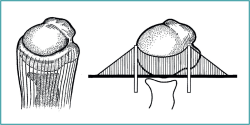

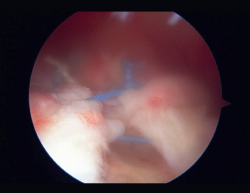

Arthroscopic partial repair was introduced by Burkhart(19) in 1994, who described the technique for restoring torque and the "suspension bridge" system of the shoulder. Understanding this concept is crucial for optimizing this type of repair (Figure 1).

The suspension bridge system was also described by Burkhart(20). In the arthroscopic view, the most distal portion of the cuff insertion has a half-moon or semicircular shape, and there are a series of thick fiber bundles at its margins that lie perpendicular to the axis of the tendon of the supraspinatus, arching from the anterior to the posterior zone to join with the humerus - an element known as the rotator cable.

In their study, Burkhart et al.(20) demonstrated that the majority of ruptures occurred more through the soft tissues than in the rotator cable, and if the latter was not affected, rupture would not be expected to extend either anteriorly or posteriorly. They found the location of rupture to be more important than its size, since a lesion involving the rotator cable is biomechanically more significant than rupture in the semicircular zone.

The relevance of this study is based on distinguishing anatomical integrity from biomechanical integrity. The partial repair procedures in massive ruptures are based on this biomechanical concept, on repair of the rotator cable.

The concept of "functional rupture of the rotator cuff" refers to an anatomically deficient but biomechanically intact cuff, i.e., a patient with functional rupture has normal function despite tendon disruption. Based on this, there are selected cases of massive rupture in which partial repair may prove useful.

The aim of partial repair is to recreate functional rupture of the rotator cuff, and this could be achieved if we are able to repair at least the lower half of the infraspinatus(19) (Figure 2).

In a more recent article, Nottague(21) reminds us that partial repair establishes balance of the torque between the infraspinatus and the teres minor in the posterior portion, and the subscapularis in the anterior portion. This torque keeps the head centered within the glenoid cavity during shoulder movement, and in patients with irreparable rupture is better than no repair.

There is no agreement as to which treatment option is best in patients with irreparable rupture, though in comparison with surgery, conservative management does seem to result in less improvement of the functional outcomes and a greater clinical failure rate(22).

The re-rupture rate of partial repair is high; according to a systematic review published by Malahias et al.(23), the figure reaches 48.9%. With this failure rate, the outcomes may be questioned, since the short term benefits may be the result of techniques that are performed simultaneously, such as debridement, or tenotomy, rather than of the partial repair in itself(24).

However, the truth is that the variability of the patient characteristics, the way in which the outcomes are evaluated, and the duration of follow-up all complicate any comparisons between different treatments(25).

Nevertheless, the studies have demonstrated high patient satisfaction and low revision surgery rates in partial repairs (2.9%) over middle-term follow-up(24). In fact, Chen et al.(26) concluded that patients with a low functional score, important pain or nocturnal pain, experienced greater functional improvement with partial repair surgery.

The most common cause of repeat surgery after partial repair is severe glenohumeral osteoarthrosis, followed by failure of repair and persistent pain. The rescue procedure in these failures is usually reverse shoulder arthroplasty(23).

Based on all the above, it can be affirmed that partial repair is a non-aggressive procedure that often improves function at least over the short and middle term, and is of greater benefit in patients with low functional demands prior to surgery. Although the re-rupture rate is high, it is common for no other operation to be needed, with favorable clinical outcomes(27).

Conclusions

There are different alternatives for the treatment of irreparable posterosuperior cuff rupture. No given technique has been shown to be superior to the rest, and among the existing options, arthroscopic debridement, tenotomy of the LPB and partial repair are safe alternatives which can afford satisfactory functional results in adequately selected patients.